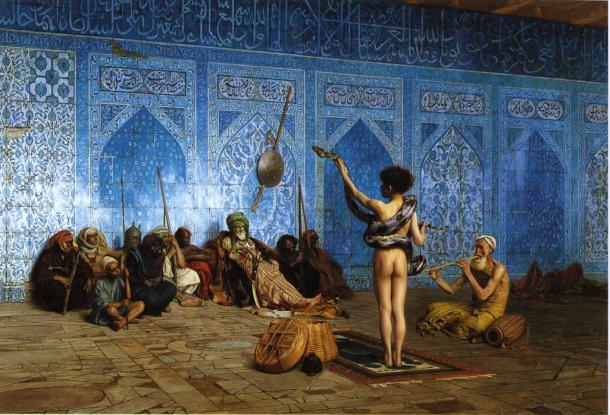

In Edward Said’s celebrated book, Orientalism, he discusses the ways in which Europeans–particularly the French and the British–imagined the East in its literature, art, and journalistic discourse, as a means of fully defining the Occident, or the West. By creating an image of the “Orient” as exotic, with its languid and eroticized culture, Europeans could imagine themselves as a rational and civilizing force whose mission was to subjugate those deemed to be “Others” to establish colonies and vast empires that would give them access to natural resources and cheap labor to achieve a kind of wealth that would sustain the growth of their industrial and capitalist societies.

Intrepid travelers such as the Venetian Marco Polo went as far as China and brought back many years of journals that would paint a lasting portrait of what we know now as the Middle East and Asia. The force of Polo’s recounting of his experience upon the European imaginary simply cannot be measured. He remained in China for seventeen years as an advisor to Genghis Khan, the fearsome Mongol leader who was the grandfather to Kubla Khan. Kubla followed in his grandfather’s footsteps in expanding the already vast empire, and with architects designed Xanadu, a famed city of sensual delights located in what is now Inner Mongolia. The Romantic British poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772-1834) awoke one morning in an opium-induced fever dream, and wrote a poem published in 1816 about this Yuan dynasty emperor and his “pleasure dome”:

In Xanadu did Kubla Khan

A stately pleasure-dome decree:

Where Alph, the sacred river, ran

Through caverns measureless to man

Down to a sunless sea.(1)

In the poem, Coleridge makes reference to sights and scents:

So twice five miles of fertile ground

With walls and towers were girdled round:

And there were gardens bright with sinuous rills,

Where blossomed many an incense-bearing tree;

And here were forests ancient as the hills,

Enfolding sunny spots of greenery.(2)

The city of Xanadu no longer exists having been destroyed by the armies of the Ming Dynasty in 1369. Through Coleridge’s poetry, the story of Kubla Khan is told by generation after generation, alive in our imaginations. Clearly, Serge Lutens and Christopher Sheldrake, the creators of the perfume Musc Koublai Khan, were similarly inspired.

The online niche fragrance shop, Luckyscent, describes the perfume with these ecstatic words:

Musk, highly evocative of the most extraordinary scents imaginable; China, precious gold, opium dens. Refinement, cruelty… senses complex in their contradictions… Koublaï Khän, the Great Mongol ruler, Emperor of China. This Son of Heaven had a hill raised in the grounds of his palace, on top of which stood a lacquer and jade contemplation pavilion. The mound was planted with rare trees, kept green whatever the season. The ground was covered with glistening malachite and lapis lazuli particles… a coating of crystal. Muscs Koublaï Khän – a sensual, undulating aura. An animalesque scent.(3)

One would think that the colonial imaginary would have disappeared with the wars that created independence for colonies in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia, and that this way of thinking about the world would be deemed politically incorrect. Somehow, it still lives on in the perfume world. In the auratic narratives Serge Lutens’ creates to sell his expensive perfumes, the Middle East is a great inspiration. Another Luten’s perfume called Chergui is named after a fierce wind that sweeps across the deserts of Africa, and Luckyscent once again waxes jubilantly over another Lutens perfume, Ambre Sultan:

It’s a trip to a Bedouin tent in a desert far away and stealing a look inside…thick incense burning on coal with spices filling the air, mysterious eyes flashing and a very real feeling that you’ve never smelled anything like this magnificent amber perfume before. A devilishly dark aroma that goes beyond sensual or coy, Ambre Sultan is flat out oozing sexuality, deeply exotic and utterly, totally and completely unforgettable. Once you smell it, it will haunt your dreams until you find your way back to it.(4)

Perfumes act upon our experiences and memories. I love incense because it reminds me of Buddhist temples; I love rose because it reminds me of my mother’s garden. But is it okay to market a product based on a rather violent history of subjugation and oppression? Do we buy into the fantasy of colonization when we buy a Luten’s scent?

I really like Lutens perfumes. They are masterful creations. However, I have a hard time swallowing the storyline that is used to sell it. Can we give the exoticism a break?

I struggle with this as well, particularly because I’m “susceptible” to the language of exoticism as well, from my early reading habits. 🙂 I just looooved the British novels from the colonial era. But I’m deeply uncomfortable with the the imagery the perfume houses put forward too (I skated around this when writing about Lyric and Borneo 1834 on my blog if you’re interested). What I find myself doing is drawing on Said and a few other critics to think about the perfumes (and/or the stories behind them) as attempts to represent the tension in environments where cultures and people are clashing and redefining themselves in juxtaposition with each other. And then I think about what the ad copy would say if they were looking at it from that perspective. 🙂

It doesn’t make me any more comfortable with the ridiculous ad copy, but it at least it makes the fact that I read the ridiculous ad copy seem like less of a waste of time!

I know I probably shouldn’t be taking this as seriously as I do. I mean, no one has banned an EM Forester or Virginia Woolf novel for being colonialist. But then again, they were writers evoking the spirit and history of their moment, while perfume companies are just selling expensive commodities. It irks me that they use this kind of language. I find the terms “Jeremy Lin” and “fortune cookie” to be offensive if used in the same sentence!

You are right–it is very much about the tension between cultures and representations of those cultures. In our globalizing world, the boundaries between us and them have almost disappeared, and until they have totally done so, marketers will continue to exploit Otherness to their own gain. *sigh* Will read about Borneo 1834 on your blog. I thought about including that perfume in this post, too, but there are so many of this ilk that I decided to lay off!

Advertising is just that: capitalizing on easy association to imprint a product with a certain identity even before the possible buyer gets a chance to try it. A game of preconceptions. Packaging is part of it too. The way I see it I have two options: either embrace the “artistic” aspect of it, void of meaning, or dismiss it all together. For me a truer name for MKK would be “Grandma’s Blanket” but I can’t imagine it attracting great sales or controversy under this name 🙂

HA! So well said. Of course you are right about advertising. I still find it rather fascinating though, be perfume is abstract, and I feel like perfumers can get away with this kind of thing more easily than, say, a fashion designer.

Modern commercial perfumery is steeped in Orientalism – there’s even a whole category of perfume characterized AS Oriental!

As a person of Asian descent (my mother’s Vietnamese) and as someone who did cultural studies and read all the theory in grad school — I totally get your critique. And I don’t think you’re taking it more seriously than it needs to be taken. It’s important to question the rhetoric of perfume’s marketing. (And it’s not like Lutens, whom I admire and whose perfumes I almost uniformly love, is living outside the colonialist fantasy in his day-to-day existence. Have you seen his home in Marrakesh?? http://www.wmagazine.com/society/2010/06/serge_lutens_ss#slide=1 )

I don’t know how to feel about it, really. Perfume is such a fantasy medium, and in some ways tapping into Orientalist fantasies makes sense. The idea that a perfume might smell like an unwashed 13th century Mongol warrior emperor from China smack dab in the deodorized, virtualized 21st century when some spaces ban any fragrance altogether — it’s almost pornographic in its transgressive allure! It’s so over-the-top that in some ways you can almost see a built-in wink of irony or self-critique. (But that could be me giving SL too much credit.)

And with Borneo 1834, Lucky Scent claims that date marks the first Western “discovery” of patchouli. I mean, these fragrances really are problematic. Sniffing them mean somehow being on the side of the colonialist, the winner, the explorer and appreciating his spoils from the exotic Other.

But like certain sexual fantasies, many olfactory fantasies are politically problematic. (Unless you recognize that? Is that enough?)

That’s all I got. No conclusion. 🙂 Thanks for the post.

I find the question of representation fascinating in perfume, simply because you can’t put an image or a feel or taste–it’s all about the narrative and language constructed around it that produces the aura. That’s why I like exploring in this blog the relationship between writing (whether it’s a review or ad copy) and olfactory experiences. Books and poetry since the 17th century at least have stirred people’s imaginations about places that they will never ever go to, or just might not want to. The journey taken by the imagination through words is quite often enough. And that’s the way perfume should be, too.

I work in the art business, and sometimes when I try to explain the work of art to someone, they say: I don’t want to know the story. I just have to like what I see. You can doll up a bottle of perfume through advertising, fancy bottles, and other frills, but it’s the juice that matters.

Yes, but the experience of the juice (for me anyway, I’m not a modernist) includes the bottle, the name, the color of the juice, and all that other stuff. MKK is complete for me, for better or worse, because it conjures up that story, gives me that name. Same with Poison and its amazing bottle (would I feel the same about it if it’d been called Flirt or Lovely, in a clear boring bottle?), etc. Perfume has a mise en scène, to me. Yes, the juice is a huge part, but we’re buying up and sniffing up other parts of the fantasy.

I was just at Krigler at the Plaza Hotel the other day (keep an eye out for the upcoming post), and one of their selling points was about the glamorous people who have worn their scents–Grace Kelly, Jackie O, the King of Jordan, etc. All of it adds to the allure because they are signifiers of luxury, taste, sophistication, and even royalty. Chanel No. 5 was famously worn by Marilyn Monroe. Who knows how many bottles of it were sold because she said it was the only thing she wore to bed!

I like thinking about this stuff, not because I’m opposed to the idea of branding since I buy into it, too, as my growing collection of bottles can attest. But I want to know WHY it’s so appealing, how advertising plays on our imaginations and possibly insecurities we have about beauty, social class, and cultural signifiers. The history of perfume is so rich and fascinating. I love it!

WOW. Perfumaniac’s link to the slide show of Serge Lutens’s obscenely opulent Marrakesh mansion put this whole discussion into a freaky sort of context. I mean, read the caption to the fourth slide: >>Serge Lutens in a courtyard with his chief houseman, Rachid. At one point Lutens had more than 500 people working on the house. “I felt like the director of the pyramid at Cheops,” he recalls.<<

And on a side note, I keep waiting for someone claiming to be from Serge Lutens to chime in, angry that bloggers aren't buying the marketing. It happened with Lubin's Marie Antoinette story for Black Jade.

I’m HOPING that the Lutens people will chime in. Bring it on!

What an interesting discussion. I realize that the perfume industry as we experience it is an Occidental contraption. And in a quite occidental way it’s either black or white. So a few years ago we decide to discover the Middle East and suddenly every dime store is filled with oud fragrances. As much as I like oud I find the whole situation hilarious.

This conversation got me wondering. Is there an Occidental genre in the “oriental” mind? And with the word “oriental” we cover a wide variety of olfactive fantasies covering cultures from the Middle East to Japan. I would be really eager to hear from someone coming from a geographically oriental culture how they define the term “oriental” in general and in fragrance in particular. And of course if there is such a genre as “occidental”.

Pingback: Eau de Sud / Muscs Koublai Khan Reviews / GIVEAWAY COMPETITION! « australianperfumejunkies